"GALATEA" - 23' Sailboat, fixed keel, wood. 23' LOA, 8' 3" beam, 3' 10" draft. Includes sail plan, lines, construction drawings, table of offsets, arrangements, inboard profile, rigging section. 4 sheets.

A tabloid auxiliary, just over 19 feet on her water line,

this little sloop will really sail. She is large enough to

carry your pals, too, so you can share your fun.

THE LURE OF SAIL is irresistible. No man who has skippered his own windjammer into the promise of a sparkling sunny morning will ever again settle for less. The sun dancing on the water, the hum of breeze in taut rigging, the powerful, quiet urge of the windâexperience all this and you'll know why sailing is called the sport of kings.

To get around the dreadful responsibility of owning a king's ransom, yet to make possible getting down to the sea in sail, I have designed Galatea. She's a tabloid auxiliary, and then, again, she isn't âshe's just large enough to avoid the wallowing tendencies exhibited by most tabloids, but not too large nor too complicated for one man to build, to afford, and to handle. Here are her main dimensions: Her length, 22'11". Her Beam extreme over deck, 8'2", and over water line, 7' 1-1/2". She draws 3'9", displaces at the line drawn 5,052 Ibs. This makes of her what our English cousins would call a 2-1/2-tonner. She lugs 285 sq. ft. of sail, perhaps a shade better, on the theory that the idea of sailing is to sail. You can always shorten down if need be, but you can't go shopping for more area when you're out on the drink.

She is knockabout rigged. That is to say she is basically a sloop, but the stem profile is extended to accommodate the jib, and there is no bowsprit.

If you're a facts and figures hound, her ballast will run to between 1,500 and 1,600 lbs. in an iron keel, with enough inboard trimming ballast battened down in lead pigs over the keel at midship to bring her down to her load line. How much will depend upon the gear carried, and somewhat on the building job. No two boats of identical design ever weighed the same: Wood varies, fastenings vary. It would be safe to say 200 to 300 lbs. would turn the trick.

Other statistics: Soakage allowed, 12 per cent. Area load water plane is 100.6 sq. ft. It will thus take 532 lbs. to burden her an inch deeper. Whence her name? This is a point all sailors are meticulous about knowing, so they can judge whether she'll be a lucky ship. Well, let me

tell you . . .

Pallas Athene was the goddess of Greek mythology who helped design the first Greek shipâthe Argo. I have heard about a curse she'd hang on any designer who doped out a vessel that wasn't right and yare.

I can't give you her tonnage nor her load water-plane area, but 'tis said by men who know such matters that this she-boss of the old Greek Coast Guard held forth up around Scylla-and-Charybdis way. She'd hoist an ample bosom upon a likely balcony overlooking the marine scene, and with a gallon in hand of the tipple of the day, she'd scan passing craft with appropriate murmurs. When she spied a schtunkpot, she'd down her 'arf and 'arf and let rip.

"Lawks, dearie!" she'd scream at the sad craft's skipper. "Where did yer get that 'orrible 'unch? She sure ain't A-l Lloyds, nor yare, nor even floating salami! A curse on 'er designer!"

Which curse henceforth struck the designer blindâand for the rest of his days he was fated to speak great truths to which no one would listen. She was a rogue, was Pallas.

I want everybody who builds to this design to get quietly past Athene, and so have named our Little Rogue obliquely in honor of the goddess from whose curse I have had some narrow escapes. It may help the boat to be a lucky one. (Note: The original name for Galatea was "Little Rogue")

She is as normal as beans and bread as to layout and rig and all. Her main gambit is in her size, and relative sail area. She is smaller than the big boats that will sail, she has more sail-carrying power than the little ones that won't. I know that this is so, because I designed her to a certain feel I wanted myself, in a modern boat of today's marconi rig. Also, I am acquainted with the classics of "Tabloidia Americana" and know their designers.

Sam Rabi and his Picaroon, my old side-kick Jack Hanna and some of his tabloids, Billy Atkin and his Perigee, Phil Rhodes and Westwind, Dr. T. Harrison Butler and Paidaâall famous designers, all famous boats. I have known both the men and the boats first hand. I am familiar with their philosophies.

Because all the craft mentioned were designed nearly a generation ago, I felt I could come up with this contribution to the field and that it would be a definite addition to the choices available.

Today the outboard motor is powerful, silent, light in weight and most certain to start. This form of poosh-em-up is used by every practical small-boat sailor I know today.

Down goes the wind, out comes the "tin breeze" from a locker somewhere, and in a trice you can rattle into port with minimum fuss. Meanwhile, in sailing, the cabin is not cluttered by an awkward foundry taking up choice space. Thus the boat's bottom is always all sailboat No dragging propeller or resistance-making open propeller port. This leaves the craft all to the wind and to slippery going. Therefore we have outboard auxiliary power.

There is no use making a boat too small. The difference in cost between an 18-footer, the cabin of which you enter only by greasing your hide, and a boat of more powerful size, say roughly 22 ft., is hardly $30 for materials if you do your own building. The footwork, thinking, and toting of materials is the same.

Therefore, doesn't it make sense to peg a size you can wear?

The sail rig of 1955 is marconi. Gaff headed rigs may look romantic, but they just aren't as efficient as a narrow, lofty rig. The "whap" in a sail is in the leading edge, the luff. Gaff rigs don't have it. More, the gaff needs a good pole mast, and this puts on topweight. The gaff is hard on sails; this calls for weighty canvas which neither sets nor draws well.

So we have marconi rig, and enough area to give some push. Weight of wind, not necessarily miles-per-hour, is what moves a boat, and this varies like the dickens, being light in August, heavy in June or October. Lower temperature, more moisture; more moisture, more weight. Miles-per-hour times weight equals whap, despite what "tables" say.

Thus the sail I have given Little Rogue will sail her. Shell not wallow around wetly like a foundered moth. If you find her tender, which I doubt, simply pile inboard ballast on until the Good Lord blows the stick out of her.

There is no icebox, for two reasons. The first is that it is impossible to drain such a box overboard. The second reason is that I won't be shipmates with an icebox that drains into the bilge to slosh around.

The resulting effluvium of such a stunt is not exactly what the barber puts on Daddy. Along about midnight in slumbrous respose you dream of elderly finnan haddie.

Better for a ship this size are a couple of chromed breadboxes of the new type which conserve moisture. These manage very well to keep meat and butter sweet until consumed, in most instances.

Potable water I'd plan to carry in canvas-covered Army canteens, which are a dime a dozen. You lose about 10 per cent of your water through evaporation, true. But cooling water with ice, you lose 100 per cent of your ice, so what's the diff?

The arrangement of this ship is standard. It may divulge no novelty, but must it? You sleep aboard, hence need bunks. You eat aboard, and hence need a galley. Also, and this is frequently overlooked, the sailor is forever accumulating gadgets and needs shelves and lockers for these. So I have left room for them. Start out with a bare ship, and you'll soon have a yare ship, as the saying goes. Usage will tell you what you want. Hence my drawing of the arrangement shows bare minimums.

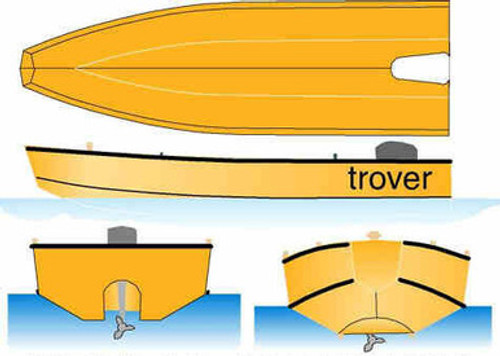

Most backyard boatbuilders seem to understand the V-bottom form of construction best, so our hull is of that form. In truth, though, a steamed, frame round-bilge boat is the easiest to build. It is so considered by most professional builders who have learned their trade at real apprenticeship. In all of the 21 yacht and shipyards in which I have punched time over the past 35 years, I never found a pro who differed.

Since steaming is generally considered one of the best tools in a boat shop, I have in the construction of Little Rogue combined the easily understood V-bottom with steam-bent frames. It is not original. Bill Hand used to design all his famed V-bottoms this way, and the system. is much used in several areas of the continent.

Steaming is the best tool in a boatshop next to the handsaw. All you need is a decent boilerânot the gas jet and tea kettle rig often hopefully picturedâbut a boiler at atmospheric pressure, like a copper washtub over a good coal or wood fire, with a pipe to the steam box, and the steam box.

The steam is at atmospheric pressure, so is safe except it must not come in contact with bare flesh. Live steam burns.

Anybody who can boil a 4-minute egg can steam-bend his frames, and will get the hang of it in one or two tries. Wear good hide gloves, and you'll soon find that steaming makes framing fast, avoiding the ocean of beveling connected with seam-and-batten construction. You do need a good steaming outfit, of course. You need a good work bench ditto, so why balk at setting up your tools?

The frames are of green bending oak, 7/8" x 1-1/2". Flat frames always tell you which way to lay them, while often square ones get bent across the grain. See that you cut the frame with the grain paralleling the flat.

In Little Rogue, the frames are spaced 9" on centers, with locations taken off the 6" spot on Frame 15.

The molds are set up as shown in the sketch called "typical mold section." The drawing tells the tale. The chine is streamed in after the main framing is bent in. Oak feathers are shimmed to fit on the outboard "corner" so the plank will have something to fasten to.

The floors are of 1-1/8" white oak. Run a line 12" from the water line toward the keel, add the 3/4" cabin-sole thickness, and lay a line at that point. This is the top of the floors.

The chine is of yellow pine, 3" wide and about 1-1/4" thick, whatever you need (depending upon your frame curvature at the bilge) to get a "corner." The filler is put in before planking and forms a rabbet. This is of yellow pine, too.

A word about the keel, before we get too far: The stem is sided 3-5/8" white oak. The cark, or gripe, is sided 6" amidships, but tapers a bit at the stem scarf. The main keel timber is of yellow pine or fir. Fir is all right and is used extensively on the west coast, whence the timbering of this boat springs from. The keel is tapered as per half siding plan on the keel erection plan. The horn timber should be of oak, sided 4".

The planking is of white cedar. Very good stuff can be secured from sawmills in North Carolina. This is ordered as 7/8"' stuff, but you'll receive 13/16" material, so I have worked up my engineering weights on that basis. Spile the plank so you get about 7 strakes from keel to chine, and about .5 from chine to sheer.

This boat planks and caulks just like every other standard hull, so I won't dwell on this oft-covered

subject.

The deck framing is rugged and simple. As is done in many yachts built in Lower California, the deck beams bear but little relation to the side frames. The main beams of the forward deck are l-3/4" x 1-1/4" white oak. The side deck beams are 1-1/4" x 1-1/4" white oak, gained to the coaming header but only half gained to the 7/8" x 2-1/2" yellow pine main clamp on which they partially rest. The coaming header is of 1-1/2" x 3" yellow pine.

The cabin sides and coaming are of 7/8" Philippine mahogany. The cabin deck beams are 3/4" x 1-1/4" white oak. Note the middle spacing is 9", and the other beams are 9" center to center. This gives an. odd spacing, but saves dividing the other frame spacings into fractions.

The decking, which goes on after the deck frame is in, is of 13/16" material. Avoid cypress, as it is heavy, but pine or spruce will be good. Cedar is costly, not needed here. The deck covers with 10-oz. canvas, laid in paint and tacked over the plank sheer edge. Of course the wood must be planed and sanded before canvas is applied.

The accommodation plan is so simple I have drawn but one side of the ship, as both port and starboard are symmetrical. The necessary off-center and off-waterline dimensions are given to enable you to size the cockpit and lay the berth flats.

The rigging plan shows both the deck arrangement in half view, and on another plate, the sail plan. To avoid cluttering up the sail plan, and thus spoiling the cogitating value of it, I have lettered the points of specification in clockwise, alphabetical order and that description accompanies the sail plan.

The rigging plan shows both the deck arrangement in half view, and on another plate, the sail plan. To avoid cluttering up the sail plan, and thus spoiling the cogitating value of it, I have lettered the points of specification in clockwise, alphabetical order and that description accompanies the sail plan.

You will have to construct a pattern for the keel, using a shrink rule which allows 1/8" to the foot, as iron, shrinks this much after being poured. No two foundries will secure the same weight from a given pattern because the mold will be handled differently in rapping and freeing. So plan on lead trim ballast inboard.

The mast is glued up of clear Sitka spruce flats and fillers which have previously been glue-scarfed. Better consult your spar maker on this. He'll be glad to give you pointers. No one should attempt this job of spar making without getting a first-hand look at professional work.

The rigging is orthodox as to standing rigging, somewhat off trail as to running rigging, but it is a style much used in a number of yachting areas and has the advantage of being uncomplicated and simple.

Anyone seriously ready to build Little Rogue can get further advice by writing me care the Boatbuilding Annual, and I may have further dope on ballast tricks by that time as no doubt several will soon be started. Stamped envelope, please!

And may Pallas Athene never let fiy at you!

WESTON FARMER